I inherited a pair of these hurricane lamps. Each one is 16 inches tall and 12 inches wide. They are labeled HN Hooper. I don’t have shades for them.

I’m wondering if I can find shades for them, if they are safe to use and – if not – can they be electrified?

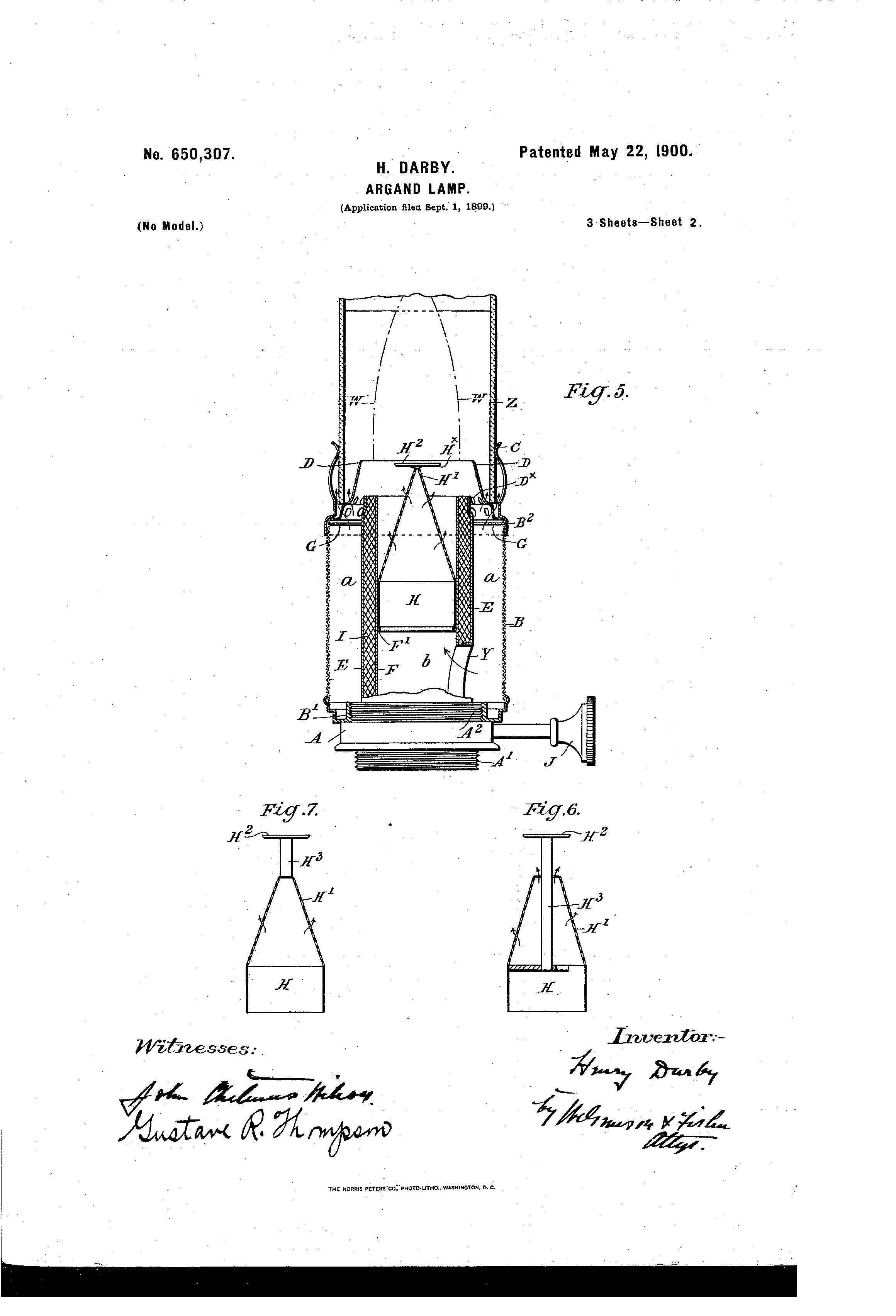

Congratulations! It looks as if you’ve inherited a pair of 2-light Argand lamps from the mid 19th century. These lamps were a huge improvement in interior lighting when they were patented in 1784. Thomas Jefferson was a huge fan and had several at Monticello.

Prior to this invention, options for interior lighting were limited to rush lights, tallow candles or beeswax candles, and oil lamps for wealthier homeowners. Tallow candles were made from animal fat: they gave poor and inconsistent light and smelled terrible. Beeswax candles produced cleaner and brighter light but were very expensive. Oil lamps were expensive and messy. Inefficient burning of the oil created sooty buildup on the glass chimneys, lessening the brightness of the lamp as an evening wore on.

Aime Argand was a Swiss chemist, physicist and inveterate tinkerer. After working with his brother developing an improved method for making brandy (and building a successful distillery), Argand combined his knowledge of physics and chemistry and invented a way to improve the basic oil lamp.

Argand developed a hollow cylindrical wick that allowed more oxygen to get to the flame creating a brighter light. He further increased the upward draft of oxygen by placing a chimney over the burner. Argand lamps burned fuel more efficiently, created less smoke, gave off vastly improved illumination and burned less oil.

Argand lamps used gravity rather than wicking to feed the flame. The central urn in your lamp would have been filled with thick, viscous oil that flowed down the arms to the burner. The downside of this central reserve was a top-heavy lamp prone to tipping over. Argand lamps were the height of lighting technology for half a century until lamps burning abundant and inexpensive kerosene replaced them.

Argand’s patent on the lamp was never respected and he never profited greatly on his invention. Companies on the continent, in England and in the US all made lamps using his technology. HN Hooper, a lightning manufacturer and retailer in Boston, was one of the biggest producers of Argand lamps in New England.

Is your lamp safe to use? To answer that you’d need to have someone familiar with the technology to thoroughly examine the reservoir and burners. You’d have to be comfortable with top-heavy lamps filled with oil burning flames.

You can certainly have them electrified, though doing so will horrify purists. In today’s market, a pair of electrified Argand lamps bring $400-700 at auction; a working and never messed with pair would sell closer to the $1000 range. If you love the idea of them perhaps you could offer to trade your pair with an electrified pair. A collector will be happy and you’ll have a pair of safe lamps.